About the Bays

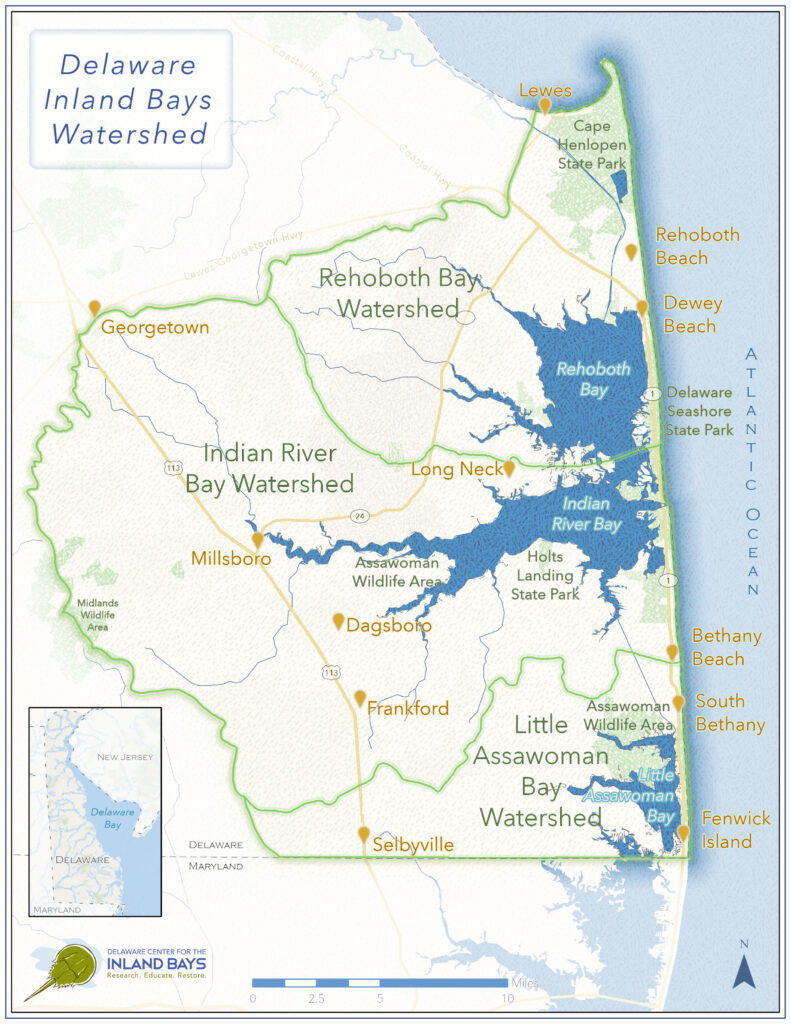

The Delaware Inland Bays are three shallow interconnected coastal lagoons in southeastern Sussex County. From north to south, these are Rehoboth Bay, Indian River Bay, and Little Assawoman Bay.

The Bays are situated behind a narrow barrier island that separates them from the Atlantic Ocean. As estuaries, they are a place where the rivers meet the sea. Freshwater flowing from the land mixes with saltwater that flows through the Indian River and Ocean City Inlets in an explosion of biological productivity. Home to hundreds of species, they are a nursery for important fish, shellfish, and migratory bird populations, making them vital to the protection of marine ecosystems in Delaware. Saltmarshes, tidal flats, forests, meadows, and saltwater creeks can all be experienced in this watershed and collectively provide immense value. Through their enhancement of tourism, outdoor recreation, and real estate, the Bays also support $4.5 billion in economic activity every year.

The Bays are shallow, with an average depth ranging from 3 to 8 feet. Because they are so shallow, and because they are poorly flushed by tidal movement, they are especially sensitive to environmental changes, including human activities and the climate. Increases in pollutants, changes in salinity, and fluctuations in water temperature, for example, can have dramatic effects on water quality and on the plants, fish, shellfish, and microscopic creatures that live in the bays.